Who Can We Trust?

Who Can We Trust

In the small island of Trinidad if you have an emergency you should call 999 – not 911, as here in Canada. Emergency numbers are meant to be the ultimate number you turn to in a crisis. In movies and television, these numbers herald in police cars, fire trucks and ambulances with EMS professionals arriving within minutes. When I first came to Canada I was in awe of this country – that it would be so well run that police would show up almost instantly when 911 was called, to serve and protect, just like in the movies. I could trust 911.

I think my family only once ever called 999 – when a trespasser climbed our fence to steal some pomeracs from our backyard tree and scared the daylights out of me as I awoke to have to giant sized eyes peering through the glass louvered windows. I called 999. My parents who were not home at the time, scolded me for not calling our neighbours or my grandmother. “Dey could be dere quicker” was the logic. Our emergency preparedness at home was to call someone you knew – not a stranger – take essentials (cash and passport being essential you anything) with you and run– don’t hide. When food shortages occurred – no potatoes, no sugar – my mother would call around family and neighbours for where to get supplies – the government wasn’t one we expected to take care of us. When the water was shut off, we didn’t call WASA the water authority to find out when next water would arrive. The husband of a second cousin who worked with someone who worked at WASA was a more reliable source. Government or public institutions could not be trusted to support you with basics in crisis: no information, no services, no one answering the phone.

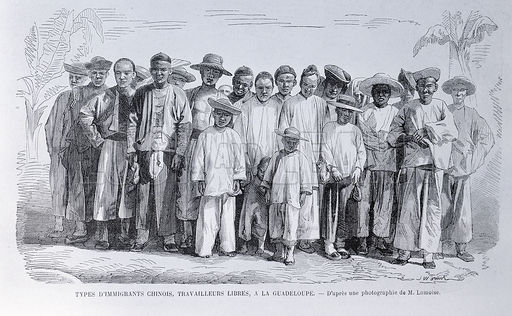

Trinidad is an island rooted in slavery and British colonialism. Public trust has not exactly been a cornerstone of our society. Those with power (starting with plantation owners) were not always interested in the well-being of everyone. My family were one of many families who between 1853 and 1866 made their way from China to the Caribbean as indentured labour for sugar and cacao plantations[1]. The first ship that made that 27,000km plus journey was aptly named the “Fortitude”. But once my family arrived, via Guyana and Martinique, they realized they could make a better living – not by cutting cane but as small traders, shop owners, laundry proprietors, and restaurant owners and cooks. Independence and resourcefulness were the guide to moving to middle management over two or three generations. No public institution came to their assistance but the kindness of others did.

My dad owned a rifle for hunting ducks, locked away in a closet chained and bolted. In 1970 with the Black Power uprising in Port of Spain, he unlocked it. Just in case he had to protect his family, as looting and vandalization had accompanied the warranted political uprising protests on anti-black racism. He knew he could not trust the 999 number. He was ready to take up arms to defend those he loved (thank goodness he never had to face that challenge).

Just last month in Trinidad, my niece and her boyfriend’s family had to fend off armed home invaders in broad daylight. She called 999 with her cell phone while the father rushed the intruders, shots rang out and the robbers ran. Minor injuries and extreme rattled nerves are in repair now but the police didn’t come until the next day. No wonder everyone there wants to live in gated communities that they can govern and control.

Today around the world many societies have been designed based on the placement of trust in others to serve the interest of the collective. A belief in the collective means that the success of others is our individual success. I still mostly hold an elevated view of public institutions– though. I am no longer as naïve to think that I can fully rely on public institutions to watch out for me.

When the pandemic struck here in Toronto, my island instincts kicked in. I ran to the nearby ATM to withdraw enough cash to survive a plane trip to somewhere else. I pulled my passport out of that bottom drawer and put it within arms-reach. When PPE and testing kits were identified as being helpful, I jumped the mark and bought a few – just in case. My Canadian born spouse called it overreacting. I thought no – just being prepared for the worst and hoping for the best.

The instinct to survive and to protect those we love is core to our human nature. This instinct is even further driven when we feel disenfranchised, excluded, and uncared for – invisible. This erosion of trust of the very institutions designed to care for us all is now tearing countries and societies apart. Too many people around the world feel unwelcomed where they live.

Today, I can get more insightful and useful information and tips from my small neighbourhood and condo Facebook groups that I can get from the daily press releases from government departments or ministries. As the 2022 Edelman Trust Barometer notes:

“With a growing Trust gap and trust declines worldwide, people are looking for leadership and solutions as they reject talking heads who they deem not credible. In fact, none of the societal leaders we track—government leaders, CEOs, journalists and even religious leaders—are trusted to do what is right, with drops in trust scores for all.”

Is it possible this is where Canada or Ontario is headed? Is this a risk that those in power are ignoring? And if so where are the solutions to treat these symptoms? Have we strayed so far that our own trust of public institutions is causing growing instability? How could this place –still one of the safest in the world – now has residents who toy with the idea owning a gun may be the way to protect themselves? This country held up as the beacon of universal health care, now has my good friend stand in-line with her husband for seven hours in the cold to get COVID booster shots.

I have seen positive and honourable leadership in action. It exists within all sectors: responsible private corporations; persistent not for profits and charities; dedicated academia; and diligent public servants, but we do not hear about their achievements or their voices often enough. They are the proof points that we can trust each other, that building a better more inclusive city and society is based on individual relationships.

Today, in my role as CEO at CivicAction, we are building the bridges that can bolster trust through one disenfranchised and sometimes deflated groups – the next generation of leaders. Every time we connect a member of our corporate establishment with a bright, ambitious rising leader, we are creating the building blocks to a more trusting society. How? Well, newcomers to the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area, approximately 110,000 annually, community organizers, post-secondary educated career builders – are driven the desire for a better future. A future that includes purpose to their chosen profession or trade, a quality of life for their loved ones to thrive..

I believe that many of the urban challenges we face is a crisis of trust. A fear that those who we should be able to turn to will not be there in our time of need, or that they will not stand for us all – but mostly themselves.

Our 911 number is a symbol of support that we have entrusted to be there for all of us in any crisis. Lets all work towards building bridges, building trust, learning from each other. In 2022, I vote for finding the things that bring us all together not what sets us apart.

[1] Today by boat it is a 14,761 nautical mile trip, about two months at sea (if you go about 10 knots).